When I was young I dreamt of getting hold of a book called Chamedan (The Suitcase) by the Iranian writer Bozorg Alavi. It was published in Tehran 75 years ago, but later it was banned, together with the writer’s other books. When I read recently that the word “suitcase” was deleted from Herta Muller’s first book in Romania, I immediately understood why.

The Shah’s censorship worked the same way, even though he was a monarch and Ceausescu claimed himself a socialist. The common denominator was their fear of literature, of words that might stir up and provoke their subjects to get rid of the authorities – or pack a suitcase and leave.

With dictators, words take on an extra charge. In the shah’s Iran the word “black night” symbolized repression and “high walls” meant prison. Words such as “blood,” “red” or “red rose” made the censor suspicious that they were agitating for revolution. Shakespeare’s Macbeth or Hamlet could not be performed at Iranian theatres as the king dies on stage!

Anyone who possessed books by Sartre or Brecht was likely to end up in Evin prison. But the censorship changes form with the times. What was forbidden under the Shah was politics, after the revolution the censorship remit was expanded to religion and sex.

Censorship is carried out in several stages. Direct censorship is done by the state – the censoring authority is under the control of the ministry for culture and Islamic guidance — while authors and publishers self-censor for political, moral and economic considerations. Despite that, everything, even a printed invitation card to a wedding, is inspected before publication. An already published book may be withdrawn from the market, even though it has been on the shelves for years and reprinted in several editions.

But how does it actually function? The writer is given a list of words, sentences and even pages of the manuscript that must be taken out. In the vocabulary of the censorship authorities this is called “negative censorship”. “Positive” censorship is when a few additional words or sentences are suggested to be added in order to make the text more moderate, or friendlier to the regime.

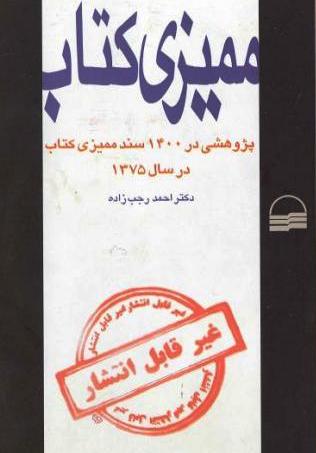

A full answer is found in Momayyezie (Book Censorship) written by the Iranian author Ahmad Rajabzadeh. I found this 600 page-goldmine at the International Library in Stockholm. It was published in Iran eight years ago and covers 1400 cases of censured books during a single year (1996). According to the book more than 75 per cent of the forbidden texts concerned the following subjects: Love, female beauty, gambling, religion.

A few examples of words that must be changed according to the censor’s suggestion can be revealing: comrade (“must be changed to ‘friend’ because Marxists use ‘comrade’,” wrote the censor), “tavern” to “café”, “in love” to “delighted”, “lover” to friend, “love-making” to “friendship”, “dance partner” to “conversation partner”, “pork” to “beef”, “wine” to “soft drink”.

Sometimes it is enough just to hint at wine. For example the poet Fereydoon Moshiri’s poem had the words, “fill the glass with glowing water” censored!

In the book we may read long lists of forbidden words and subjects. Among the censored words we find: discotheque, prostitution, rape, homosexuality, descriptions of venereal diseases. The words “That night my daughter had her first period” were crossed out of one manuscript by the censor. Another censor found the phrase “wedding night” to be offensive to society.

The sentence “She in her dress of red velvet and a white scarf was more beautiful than a red rose” was censored: a photograph of Gandhi was objected to. The censor wrote: “take away the photo, he is half naked.”

Sometimes their edits are absurd, of course kissing may not occur in literature in Iran, but in one novel the following sentence was crossed out: “He kissed his money!” “Dance” is another forbidden word; instead one should write “rhythmic movement.”

How are foreign books censored? Kafka’s Metamorphosis remarks on ten points, use of words such as: “wine”, “beer”, “embrace”, “fall in love” … The censor wrote: “Under prevailing conditions the book is not suitable for publication.”

But Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is forbidden for different reasons: “The book arouses thoughts of suicide in the face of adversity instead of resistance and patience … The individuals of the novel show bad and weak features of character.”

The first 5,500 copies of the Persian translation of Gabriel García Márquez’s Memoirs of my Melancholy Whores sold out in three weeks, but after a short notice in the fundamentalist paper Jomhuriye Eslami, permission to print a second run was withdrawn. The minister of culture made a public apology for the book having been published at all and promised to punish and to dismiss the official who had let it happen.

In the year 2008 the annual congress of International PEN highlighted the case of the Iranian writer Yaghoub Yadali, jailed for 41 days in jail because in his novel Adabe Bigharai (The Ritual of Restlessness) a married woman has a relationship with another man.

Censorship in Iran is now more extensive than ever before. Book Censorship exposes the fear and weakness of those in power. The censors forgot to censor that one.

Azar Mahloujian is a member of board of the Swedish PEN, he comes from an Iranian-Swedish background

Published originally in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter

Translated by John Meurling

http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2010/02/iran-censorship-books/